Searching for Balance in an Underwater World Gone Upside Down by Song K Hunter

For many locals in our Northern California community, reading that we are in the midst of a devastating imbalance within our Pacific coastal intertidal zones will not come as a surprise. This is due to a chain of events spanning almost 200 years. This story is one of ripples, spreading ever outward: one imbalance leads to another, and another.

To learn the history of Fort Ross is to know the plight of the sea otter and to understand how the effects of our human practices can have long term, sometimes catastrophic results. The Sonoma Coast has had a regional extinction or extirpation of sea otters for the last 100+ years, since the Russian, American, and British over hunted the animals. These furs were so valuable that a hunter could earn a year’s salary with just one pelt.

The sea otter is an apex predator. It consumes 20 to 30 percent of its body weight daily, helping to keep other species under control. The sea otter has been gone from Sonoma Coast for over 100 years, but it was a series of subsequent events that caused our ecosystem to crash.

It started with a severe algal bloom, or red tide, in 2011, during which Fort Ross’s abalone population was hit particularly hard. Then in the summer of 2013, our coast was hit by one of the largest die-offs of sea stars that scientists had ever seen. For the next two years, 2014 and 2015, our coasts continuously saw the warmest water on record due to the “Warm Blob” and a strong El Niño. These warm waters led to a massive bloom in purple sea urchin.

All these events, individually, may not have had a great impact, but together, they’ve created what CDFW calls the Perfect Storm. Even today, our waters continue to stay far warmer than in previous years, leaving room for the wasting disease and urchin populations to thrive. These are very clear signs of our rapidly changing climate.

Photo caption: Aftermath of the harmful algal bloom: dead abalone and other invertebrates washed up on shore at Fort Ross in 2011. photo by N. Buck

One of the main species hit by the sea star wasting syndrome was the Sunflower Star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) and it was this species, along with the Ochre Sea Star (Pisaster ochraceus), that had been keeping the population of the Purple Sea Urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) in balance.

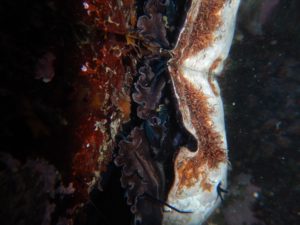

With few remaining natural predators, the now massive urchin population has transformed the sea floor into what are called urchin barrens. These fields of urchins have decimated their favorite meal, Bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana).

photo by Jeanne Jackson

Bull kelp is a beautiful species of seaweed that grows seasonally, at times in Spring, up to ten inches a day. Its canopy is focused at the ocean's surface, as each stipe (stalk) ends in a gas filled bulb. Each bulb has many leaflike blades, sometimes over three meters long! It provides a sanctuary for fish and a food source to hundreds of species.

Since 2013, the Mendocino and Sonoma coasts have seen a 93% decrease in our Bull kelp forests. According to the Noyo Center’s Bull Kelp Recovery Program, “Fewer fish has meant that shore birds do not have enough food for their chicks. This year, 90% of the local cormorant and 80% of the black oystercatcher nestlings failed to survive. Fewer young fish also means fewer larger fish for marine mammals, such as harbor seals and sea lions.”

The next species hit by this story of ripples is the Red abalone (Haliotis rufescens). They have now lost their primary food source, the Bull kelp. Over the last four years, we have seen thousands of Red abalone wash up in Sandy Cove. Searching for a new food supply, they travel higher and higher in the intertidal zone, but they are not finding enough to remain strong and healthy and, as a result, are dying en masse.

The Red abalone population is dying in such high numbers that the CDFW has closed the entire California abalone season until March of 2021. This puts a strain on the commercial industry. There are many whose livelihoods depend on the income brought in from harvesting abalone, but this minor pause on the ‘take’ of abalone is essential to the preservation of the species.

The number one question I am asked as an educator is: why don’t we reintroduce sea otters? After speaking with Environmental Scientist Dr. Cynthia Catton of CDFW, I have a much better understanding of why this is not a simple fix to this complicated, multifaceted problem. To start, we seem to be too far into this imbalance to ‘throw’ sea otters into the mix. While sea urchin can be a favored food of some sea otters, at this point, even the urchins here are starving, so the nutritional value they would offer is minimal. Otters would only take the urchins still able to find food, on the edges, leaving all the barrens.

Additionally, otters learn what to eat from their mothers. If an otter’s mother does not eat urchin, then that otter also does not eat urchin, so reintroducing otters who might not even eat urchin would only put other species like the starving abalone at risk.

While it does seem bleak, there are things that we can do. It turns out, we may be the predators needed in this complicated tragedy.

Current research aims to create a new commercial purple urchin market by making agricultural compost out of their harvested tests (their hard outer body). For individuals, the daily bag limit used to be 35 urchins/person. Now the take is forty gallons a day, which is eight, five-gallon buckets. Their outer body is nearly pure calcium, adding excellent nutrients for soils. Collecting urchin, individually, or in groups, could help put a dent in the urchin overpopulation.

Most importantly, one of the biggest things you can do is help to spread the word. Be an educator! Both the Greater Farallones Association and the Noyo Center have excellent Kelp Recovery/Restoration programs and Fort Ross Conservancy continues to educate people about this issue. Together, we can make a difference.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” -- John Muir

To learn the full story, read California Dept. of Fish and Wildlife’s “The Perfect Storm” article.

Song K Hunter, Director of Programs

Mendonoma Sightings

Nature sightings on the Sonoma/Mendocino Coast